From a talk at the Mellor Archaeological Trust Christmas lunch, December 14th, 2014, given by John Hearle

In the of the middle of the 17th century,100 years before Oldknow was born, cotton was hardly known in Britain, except what came from places like India. In his great book, The History of the Cotton Maufacture in Great Britain, Edward Baines quotes from the travels to India of the merchant, Tavernier, in the middle of the 17th century.

"There is made at Seconge a sort of calicut so fine that when a man puts it on, his skin shall appear as plainly through it, as if he was quite naked..…the governor is obliged to send it all to the Great Mogul's seraglio…to make the sultanesses and noblemen's wives shifts for the hot weather ; and the king and the lords take great pleasure to behold them in these shifts, and see them dance with nothing else upon them."

Baines comments on the spinning of fine yarns:

“The spinster keeps her fingers dry by the use of a chalky powder. In this simple way the Indian women, whose sense of touch is most acute and delicate, produce yarns which are finer and far more tenacious than any of the machine-spun yarns of Europe.”

“The spinster keeps her fingers dry by the use of a chalky powder. In this simple way the Indian women, whose sense of touch is most acute and delicate, produce yarns which are finer and far more tenacious than any of the machine-spun yarns of Europe.”

The weaving was also quite primitive. Baines again:

“The yarn is given to the weaver, whose loom is as rude a piece of apparatus as can be imagined….the weaver carries [it] to a tree, under which he "digs a hole large enough to contain his legs…He then stretches his warp…..by fastening his bamboo rollers…on the turf by wooden pins…[the rest] he fastens to some convenient branch of the tree over his head…two loops…in which he inserts his great toes, serve instead of treadles; and his long shuttle draws the weft through the warp, and afterwards strikes it up close…He is obliged to work continually in the open air; and every return of inclement weather interrupts him.”

By 1700, the East India Company was becoming more powerful and much of what was called muslin was diverted from the Mogul Court to the royal court in England – and then more widely.

The trade was very profitable for the East India Company. There was no competition until two 20-year olds in Lancashire decided to challenge it. Samuel and Thomas Oldknow organised spinning of fine yarns using Crompton’s mule, which was first known as the Muslin Wheel, and then putting out the work to hand-weavers and selling the cloth through a London merchant, Samuel Salte.

Their muslins were prized by the fashionable ladies of the time. But plain fabrics did not satisfy them. Oldknow had his weavers produce figured muslins. In 1784, Salte wrote: “Vary the spot Barleycorns, leaves and other little fancy objects… we do not despair of great attainment in this branch of the trade, Ingenuity, and patience and perseverance will yet work miracles.”

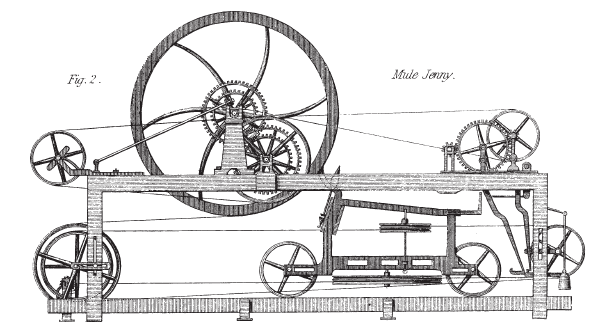

Cromptons manually operated mule.

The brothers  did very well by working with Samuel Salte. On April 19, 1786, he wrote “Yesterday we sent you £200 by Pickford”. If we convert that to current value, you cannot imagine sending £26,000 by a Pickford’s van.

did very well by working with Samuel Salte. On April 19, 1786, he wrote “Yesterday we sent you £200 by Pickford”. If we convert that to current value, you cannot imagine sending £26,000 by a Pickford’s van.

Why was Oldknow so successful? In his book, Samuel Oldknow and the Arkwrights: Industrial Revolution in Stockport and Marple, Unwin writes: “Our records not only confirm the tradition that Oldknow was the first successful maker of British muslins, but seem to show that he owed his success to creative aesthetic gifts than to mere business shrewdness”. There were earlier attempts and Unwin adds: “It is not impossible that if all the facts were known, we should have to attribute greater merit in the origination of the manufacture to Thomas Ainsworth of Bolton, to Joseph Shaw of Anderton, or to some mute inglorious weaver of Paisley who struggled in vain against the more adverse conditions of an earlier time”.

But there are downsides to the story of muslin.

In Advantages of wearing Muslin Dresses! (1802), James Gillray caricatured a hazard of untreated muslin: its flammability.

I found another quote on Google.

[In France] “in the early 19th century, the fashion trend changed from the fancy dresses of the past with many decorations to a much more simple, clean and frugal type of dress…women wearing petticoats … [which] puff out skirts…were even executed on the guillotine…to follow the fashion it [was] not enough to simply wear a muslin dress….the trend was to douse your dress in water….the very thin and light cloth becomes half transparent when wet, while clinging to your body. Women dampened their muslin dress to prove that they were wearing nothing underneath. Also, the ideal, beautiful woman of the time was an intellectual woman who looked fatigued from reading books all night long. Drenching yourself in water adds to this gaunt image, accentuating your fatigue and by extension, your beauty. The women probably also intended to make the clothing cling to their body to show off their figure (much like the modern day wet t-shirt contests).”

[In France] “in the early 19th century, the fashion trend changed from the fancy dresses of the past with many decorations to a much more simple, clean and frugal type of dress…women wearing petticoats … [which] puff out skirts…were even executed on the guillotine…to follow the fashion it [was] not enough to simply wear a muslin dress….the trend was to douse your dress in water….the very thin and light cloth becomes half transparent when wet, while clinging to your body. Women dampened their muslin dress to prove that they were wearing nothing underneath. Also, the ideal, beautiful woman of the time was an intellectual woman who looked fatigued from reading books all night long. Drenching yourself in water adds to this gaunt image, accentuating your fatigue and by extension, your beauty. The women probably also intended to make the clothing cling to their body to show off their figure (much like the modern day wet t-shirt contests).”

“Considering that women were wearing such a thin dress and even pouring water on themselves, one can imagine how cold they must have been. In fact, France suffered a heavy epidemic of pneumonia in the early 19th century with as much as 60,000 patients turning up with pneumonia every day. A high proportion of these patients were women who liked to wear wet muslin dresses. Thus, the pneumonia was nicknamed muslin disease.

So the Oldknows have something to answer for.